Eigenvector centrality

Complex networks is a common name for various real networks which are usually presented by graphs with a large number of nodes: Internet graphs, collaboration graphs, e-mail graphs, social networks, transport networks, protein-protein interaction networks, and many other.

The term network analysis refers to a wealth of mathematical techniques aiming at describing the structure, function, and evolution of complex networks. One of the main tasks in network analysis is the localization of nodes that, in some sense, are the “most important” in a given graph. The main tool to quantify the relevance of nodes in a graph is through the computation of suitably defined centrality indices. Many centrality indices have been invented during time. Each one of them refers to a particular definition of “importance” or “relevance” that is most useful in a given context.....

Eigenvector centrality 101

Ranking the nodes of a network according to suitable “centrality measures” is a recurring and fundamental question in network science and data mining. Among the various network centrality models, the class of eigenvector centrality is one of the most widely used and effective. This family of models dates back to the 19th Century when it was proposed as a mean to rank professional chess players by Edmund Landau1 and was then popularized in the network science community starting from the late ’80s with Bonacich2, PageRank3 and HITS4 models.

This class of scores assigns importances to the nodes of a graph, based on the leading eigenvector \(x\) (or the leading singular vectors \(x,y\)) of suitable network matrices and strongly rely on the matrix Perron-Frobenius theorem. One of the keys of the success of eigenvector centralities is that they naturally incorporate mutual reinforcement: important objects are those that interact with many other important objects. To clarify this idea, we review below two widely used centrality models (we consider the case of binary “unweighted” graphs for simplicity, but everything transfer with minor adjustments to the weighted setting.)

Bonacich centrality Let \(G=(V,E)\) be a graph with adjacency matrix

where \(j\to i\) means that there is an edge in \(G\) going from \(j\) to \(i\). Bonacich centrality model defines the importance \(x_i\) of node \(i\in V\) as

that is, the importance of node \(x_i\) is linearly proportional to the importances \(x_j\) of the nodes that points towards \(i\). The Perron-Frobenius theory teaches us that, if the graph is strongly connected, only one such vector \(x\) exists, the Perron eigenvector of the adjacency matrix \(A x=\rho(A)x\), and it provides us with sufficient conditions to compute such \(x\) via the simple Power Method scheme.

HITS centrality Another widely used approach defines two centralities indices, the hub score and the authority score, via the mutual reinforcing informal idea that “a node is a good hub if it points to good authorities; and a node is a good authority if it is pointed by good hubs”. If \(x_i\) and \(y_i\) are the hub and the authority scores of node \(i\), respectively, then

Again, by the Perron-Frobenius theorem, if the graph is strongly connected there is only one nonnegative solution, the dominant left and right singular vectors of the adjacency matrix.

Nonlinear eigenvector centrality

While powerful and useful, these models have two main drawbacks:

- they only allow for linear proportionality relations to define the importance model

- they may not be unique, even for simple graphs

The nonlinear Perron-Frobenius theory allows us to overcome both these two drawbacks in a very natural way. This will be particularly important when moving to the case of higher-order networks, as we will discuss next. Here we discuss two simple illustrative examples.

Suppose \(A=I\) is the identity matrix. This is certainly not irreducible and in fact \(Ax = x\) for all nonnegative vectors \(x\in C_+\). While from a linear algebra point of view there is no preferred nonnegative solution to \(x=Ax\), from the graph centrality perspective this is not the case. The graph of \(A\) is a set of isolated nodes, each with a self-loop of weight exactly one. Thus, a centrality score for these nodes would assign same score to all the nodes. This corresponds to the eigenvector \(x = \one\) of \(A\). While this is only one of the nonnegative solutions of \(x=Ax\), \(\one\) is the only nonlinear Perron eigenvector of a “nonlinear version” of the eigenvalue problem for \(A\). Precisely, consider the nonlinear eigenvalue equation

It is easy to verify that the mapping \(F(x) := Ax^{1-\varepsilon}\) is (multi)homogeneous with homogeneity matrix the scalar \(\M=1-\varepsilon\). Thus, for any \(\varepsilon \in (0,1)\), \(\rho(\M)<1\) and by the nonlinear Perron-Frobenius theorem we have that \(\eqref{eq:Af(x)}\) has a unique positive solution. It is easy to verify that such solution is entrywise constant, yielding the desired centrality assignment.

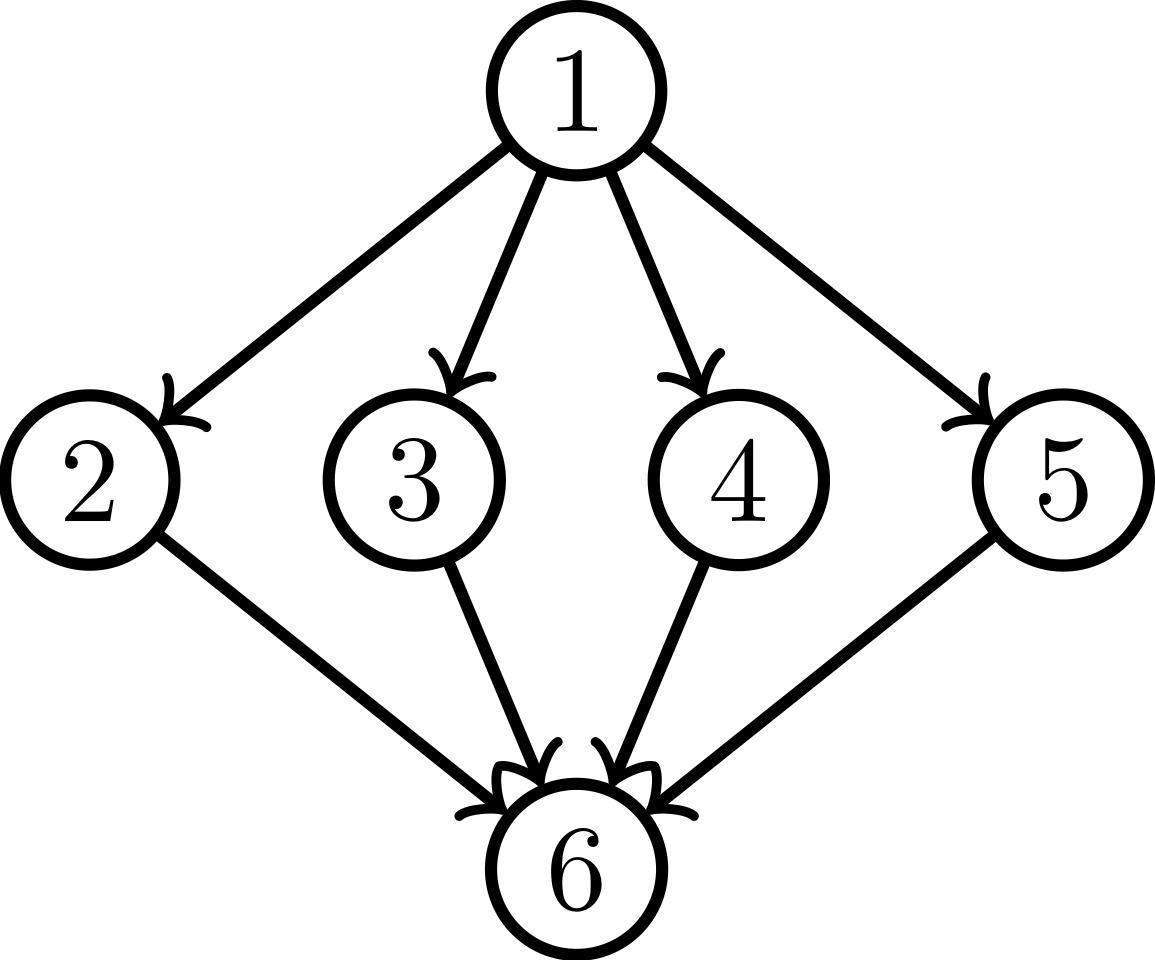

A similar situation holds for the singular vector case. Consider the graph in the figure below:

This is a well-known example where HITS centrality may fail to output a reasonable centrality. While this graph is not a strongly connected graph, we all most probably agree that node \(1\) is the most relevant hub while node \(6\) is the most relevant authority. Despite this simple setting, using the dominant singular vectors of \(A\) as in the HITS model may fail to identify these relevant hub and authority nodes. In fact, for example, both the following pairs

are (up to scaling) singular pairs of the dominant singular value of \(A\). This shows that, in the first case, the hub vector fails to detect that node \(1\) is a better hub than nodes \(2\)−\(5\). Similarly, in the second case, the authority vector fails to identify node \(6\) as a the best authority. Also in this case, a small nonlinear modification of \(\eqref{eq:sing-vec}\) solves this issue. Consider the singular vector equation

It is easy to see that any such pair of vectors is an eigenvector of a multihomogeneous mapping with homogeneity matrix

Thus for any \(\alpha\beta<1\) the nonlinear eigenvector equation \(\eqref{eq:nonlin-sing-vec}\) has a unique solution. Below we show the value of the two solution vectors \(x,y\) for different choices of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), showing that these two vectors capture the actual roles of nodes in this example graph.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

-

J. P. Schäfermeyer. On Edmund Landau’s contribution to the ranking of chess players. Technical Report, Unpublished manuscript, 2019. ↩

-

P. Bonacich. Power and centrality: a family of measures. American Journal of Sociology, 92:1170–1182, 1987. ↩

-

Lawrence Page, Sergey Brin, Rajeev Motwani, and Terry Winograd. The PageRank citation ranking: Bringing order to the web. Technical Report, Stanford InfoLab, 1999. ↩

-

Jon M Kleinberg. Authoritative sources in a hyperlinked environment. Journal of the ACM \(JACM\), 46\(5\):604–632, 1999. ↩